As a worldschooling family, we often encounter places and stories we’ve never fully understood before stepping into them. The Crazy Horse Memorial was one of those stops. At first glance, it seemed like another roadside attraction—a massive sculpture of a figure I’d vaguely heard of. But as we stepped inside and started piecing together its story, the experience became something much more profound, unsettling, and thought-provoking.

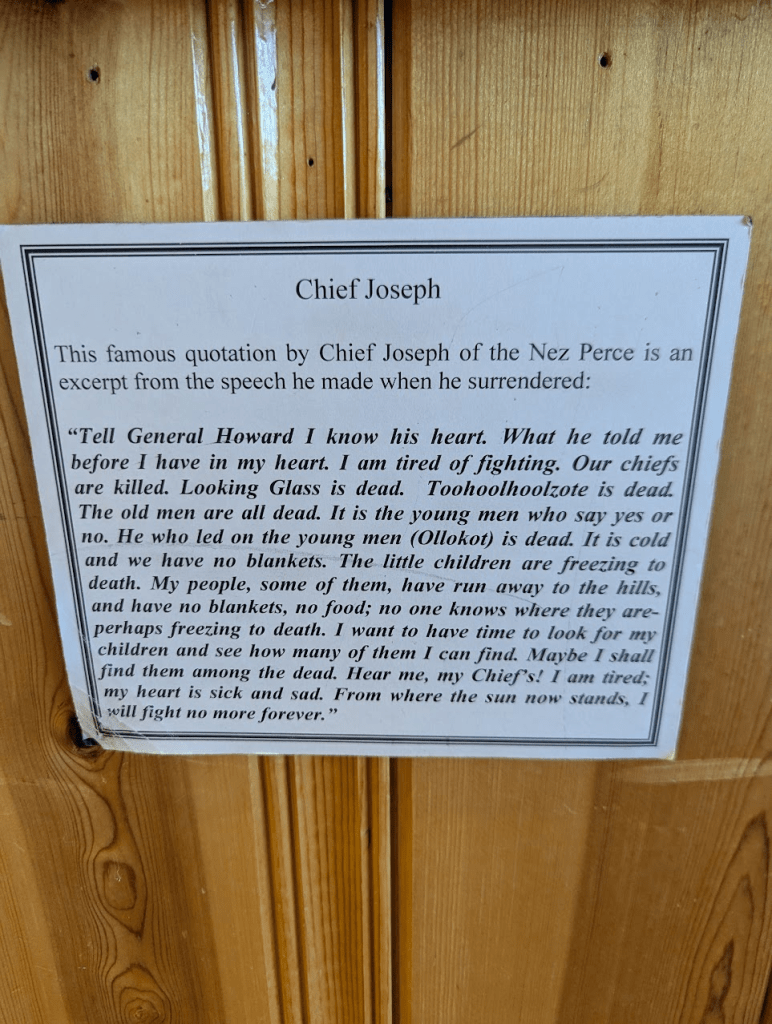

Crazy Horse. Even the name felt odd to me, almost comical, yet I quickly realized the weight of what it represented. This wasn’t just a giant rock carving; it was a story of resilience, of a people pushed to the brink and fighting to preserve what little was left. Crazy Horse wasn’t some abstract figure—he was a leader who resisted colonization and refused to give in, even in the face of relentless oppression.

But as I walked through the museum, I couldn’t shake a deep sense of conflict. The U.S. flag flying over the site felt out of place. Here we were, standing on sacred land, reading about the atrocities committed against the Indigenous people—the massacres, the land theft, the systematic destruction of their way of life—yet surrounded by symbols of the very system that had oppressed them. What did it mean to celebrate Crazy Horse in this context? Was this memorial an act of healing, or just another layer of appropriation and control?

The sculpture itself is awe-inspiring but unfinished, and I couldn’t help but wonder why. Eighty years to carve a horse? Why so slow? And then I thought about the narrative being crafted here. The museum was staffed mostly by Americans, from the janitor to the people selling tickets. It felt like a machine, not a living, breathing tribute to a culture that had endured unimaginable suffering. What was their connection to this story? Did they see themselves as part of the legacy of colonization, or were they just passing the time, working a job?

Then there were the cash booth questions, asking visitors what tribe they belonged to or if they identified with any. It felt performative—like a nod to inclusion without really addressing the weight of what had happened here. I left with more questions than answers. Was this memorial a genuine effort by Indigenous communities to reclaim their history? Or was it another way for the colonizers to shape the narrative?

I found myself explaining these questions to my kids as we walked back to the car. We talked about resilience—about how Crazy Horse’s story is one of defiance and survival. But we also talked about the messiness of history, about how the stories we’re told are rarely simple. Visiting the Crazy Horse Memorial was a lesson in contrasts: the beauty of the sculpture against the ugliness of the history it represents, the pride of the Indigenous people against the lingering presence of the oppressors.

In the end, the visit wasn’t just about learning what happened—it was about wrestling with what it means to preserve history and who gets to tell the story. For us as a worldschooling family, it was a reminder that education isn’t about easy answers. It’s about diving into the complexity, asking hard questions, and sitting with the discomfort of not knowing.

Leave a comment